When ExxonMobil Research & Engineering announced in January that it had awarded Lockheed Martin a contract to act as lead system integrator for the development of a next generation process automation system, it had many pundits in the process automation community (including yours truly) scratching their heads. Sure, Lockheed Martin helps create mission critical systems for aerospace and defense, but what do they know about controlling an oil refinery?

But as I’ve come to understand more details of ExxonMobil’s vision, I see the choice as both inspired and potentially disruptive. Consider a recent soundbite: “Innovation is being stifled by legacy architectures and hardware that just can’t be that responsive.” This quote isn’t from anyone at ExxonMobil or in the process automation sector, but from U.S. Navy leadership. Indeed, the armed forces face many of the same challenges that companies like ExxonMobil do: aging, monolithic, proprietary systems that are both expensive and inflexible.

“It’s too difficult to replace a distributed control system (DCS), and we’re not getting enough value from them,” said Don Bartusiak, chief engineer, ExxonMobil Research & Engineering, in keynote remarks at the ARC Advisory Group’s Industry Forum earlier this month in Orlando. The company faces global growth and competition yet must lower capital costs and improve profitability, Bartusiak said. “We have opportunities with finite windows.”

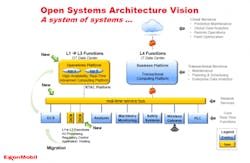

ExxonMobil envisions a new "system of systems" that will allow it to more easily adapt its operations environment to change needs and opportunities.

Much like private industry, the U.S armed forces are under pressure to protect their systems from cyber attack, as well as stay one step ahead of adversaries in the physical world. An important step forward has been The Open Group’s Future Airborne Capability Environment (FACE), a consortium of avionics industry participants formed in 2010 that has worked to create an open avionics standard for making military computing operations more robust, interoperable, portable and secure.

Consider Lockheed Martin’s leadership role in what Bartusiak called this “constructive revolution” in avionics, together with a need for more “systems engineering capability with real-time, deterministic, high availability open systems,” and the selection of the relative outsider to help shake up the process automation status quo makes a ton of sense.

End users of process control systems such as ExxonMobil are looking to benefit from larger technology trends such a virtualization and open architectures; to derive value from Internet of Things, wireless and cloud services models; and to leverage emerging security models that enable more secure data flow between the operational technology and IT/cloud layers of the enterprise, Bartusiak said.

In the end, ExxonMobil envisions prototyping in 2016 and deploying in 2019 a standards-based, open, secure and interoperable control system that:

- Promotes innovation & value creation;

- Effortlessly integrates best-in-class components;

- Affords access to leading-edge capability & performance;

- Preserves the asset owner’s application software;

- Significantly lowers the cost of future replacement; and,

- Employs an adaptive intrinsic security mode.

Further, the fruits of this effort should be applicable to both brownfield and greenfield facilities as well as a commercially marketable system (not exclusive to ExxonMobil) that is applicable to all current DCS markets, Bartusiak said.

Just substitute “process automation” for “avionics” and “chemical plant” for “Army aircraft” in the following statement on the FACE website by Brigadier General Bob Marion, program executive officer for Army Aviation: “I see [FACE] as a viable strategy for promoting competition and lowering barriers for prime and third-party vendors to insert new avionics technology into our Army aircraft….[It] incentives modernization and promotes competition by creating opportunities for all potential avionics suppliers.”

If you’re an end user of distributed control systems – or a supplier of them reliant on existing business models – it’s pretty easy to see both the opportunity and the threat going forward.