By Jonathan Katz

Craft beer enthusiasts can be a tough bunch to please.

They may notice subtle differences in flavors from one brand or style to another. And aficionados often share their opinions about their experiences on beer review sites and message boards. Their demand for high-quality product has at least one brewer rethinking how the company tracks and traces ingredients across its supply chain.

Alpha Acid Brewing Co. in Belmont, California, is using sensors connected via the Internet of Things (IoT) technologies together with a blockchain platform from Oracle Corp. to increase transparency about the harvesting and transportation of its ingredients, says owner Kyle Bozicevic.

“We see these technologies as having the potential to transform brewing, enabling brewers to evolve the craft and create new styles of beer as a result of increased access to brew data,” Bozicevic says. “We also see a trend with consumers where people now want to know what’s in their food. This trend is particularly relevant in craft brewing where ingredient origins help to sell beer.”

The food and beverage industry is among the leading sectors driving the push toward the “autonomous supply chain.” This is a “self-governing, self-ruling, self-optimizing” supply chain that uses a network of sensors, artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning and blockchain to provide a trusted record of every transaction or hand-off along a product’s journey, says Mark Morley, director of strategic product marketing for enterprise information management software company Open Text Corp.

The autonomous supply chain will increase trust, reliability and visibility for manufacturers, their partners and customers, experts say. It’s rooted in technologies that have already transformed the consumer market, such as global positioning systems, says Ralph Rio, vice president, enterprise software, technology research and advisory firm ARC Advisory Group.

“It boils down to taking consumer electronics—software that’s a part of our smartphones—and applying it in the industrial space,” Rio says.

For example, in cold-chain applications, which involve temperature-sensitive products, sensors inside trucks can send data about conditions that may impact freshness or perishability to the cloud. The next step in the journey toward a truly digital supply chain is making this data immediately accessible across the entire network via blockchain technology, Rio says.

Several sectors, including the food and beverage, automotive and pharmaceutical industries, have already launched major collaborative initiatives around supply chain data-sharing.

Keeping recalls in check

Recalls have been a costly problem for the food industry. In 2018, several E. coli outbreaks forced retailers to pull all of their romaine lettuce from shelves. The IBM Food Trust is one of the more prominent blockchain initiatives in the industry that could reduce the time it takes to identify a contamination source.

The Armonk, New York-based tech giant launched the initiative in October 2018 to establish a reliable record about the flow of goods, money and information from the farm to retailers and back, says Ramesh Gopinath, vice president of supply chain solutions, IBM Blockchain. Early partners include major manufacturers and retailers, such as Walmart, Kroger, Tyson Foods Inc., Nestle and Unilever.

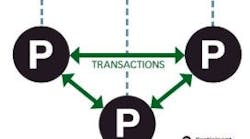

The primary benefit of the blockchain network is the replacement of a central authority for data access with peer-to-peer networking, Rio says. “What happens with a central authority is that the data is siloed and not readily available to the supply chain participants,” Rio says. “And there may be multiple central authorities, so each one has separate siloed data, which makes coordination through the supply chain and gaining visibility problematic.”

Companies participate in the Food Trust by signing up for a subscription and then exporting their data, including inventory lists, order records and supplier information, from existing data storage centers, such as an ERP system. Once they’re in the system, Food Trust participants can locate items from the supply chain in real time by searching for food product identifiers—such as the Global Trade Item Number or Universal Product Code—entering the product name, and filtering their searches based on dates, according to IBM.

In the early stages of the Food Trust, onboarding costs for companies joining the network were about $100,000, Gopinath says. That cost has decreased significantly to about $30,000 for larger companies and as low as $3,000 for smaller organizations, according to Gopinath.

Want more? Find all of Smart Industry's supply chain features here.

Real-time results

IBM and Walmart already realized the potential of blockchain to quickly identify the origin of a product during a simulated recall. They tested how long it would take to figure out where a batch of mangoes came from. They decreased the time it took to trace the mangoes from seven days to only 2.2 seconds, according to Rio.

For manufacturers blockchain should improve their ability to find and correct contamination issues before they become a larger problem. For example, if Walmart reports a problem with a tub of vanilla ice cream to Nestle, Nestle can use the batch or lot number to pinpoint where the ice cream came from, including the specific plant, vanilla supplier and dairy farm, Gopinath says.

The process allows manufacturers to reduce the size of the recall to only the contaminated area. This means they don’t have to scrap more product than is necessary, and they save on labor costs related to identifying the source, Gopinath says.

The pharmaceutical industry is another sector that’s using blockchain technology to improve product traceability. Enterprise software provider SAP announced the launch of its blockchain-based Information Collaboration Hub for Life Sciences in January to help the industry comply with new counterfeit-prevention regulations. The U.S. Drug Supply Chain Security Act requires that by November 2019 wholesalers identify any returned prescription drugs that are intended for resale. The mandate is intended to protect consumers from fake, contaminated and stolen medication.

SAP developed the software with several pharmaceutical wholesalers and manufacturers, including AmerisourceBergen Corp., Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline plc and Merck & Co. Inc.

Complying with the mandate could be challenging with the large volume of returns that the industry handles. U.S. wholesalers encounter nearly 60 million returns annually, accounting for an estimated $7 billion, according to SAP. Wholesaler AmerisourceBergen works with about 450 pharmaceutical manufacturers, says Jeffery Denton, senior director of Global Secure Supply Chain at AmerisourceBergen.

Each returned pharmaceutical product has unique identifiers, such as a serial number, batch and expiration date, that AmerisourceBergen must verify with the manufacturer before the company can redistribute it. SAP’s blockchain network allows the company to message the data to the manufacturer in “sub-second response time” and have the manufacturer confirm that it produced the product based on the unique identifiers, Denton says.

Strategic advantages

Digital track-and-trace capabilities could transform many other critical functions across the supply chain, including contract management, innovation and customer relationships. For instance, customers may want to know the products they’re buying are meeting certain sustainability or dietary standards.

Provenance tracking—sometimes described as a “digital passport”—can confirm the authenticity of product claims, such as certified organic or antibiotic-free. A standards organization can upload certifications related to specific products into the blockchain where that information can be shared throughout the supply chain and eventually to the consumer, Gopinath says.

For instance, in Spain, customers of French retailer Carrefour SA can use their smartphones to scan the QR code on a package of chicken and see where the chicken comes from, where it was reared or the methods used to produce it, according to the company.

Similarly, Alpha Acid Brewing customers may want to know ingredient origins, Bozicevic says. “People like the idea of trying a beer with Motueka hops in it,” he says. “But how do they really know those hops were grown in Motueka (New Zealand)? Blockchain solves this problem and helps prevent false claims being made about what is in a product.”

Another potential benefit is the ability to streamline the processing of supply chain contracts, such as change of ownership, proformas, bills of lading, payment terms and letters of credit, says John Barcus, vice president of manufacturing for Oracle. Blockchain enables the creation of smart contracts. These documents are written in computer code with embedded rules and actions that execute and enforce an agreement. When a transaction occurs, the system applies the rules in the code and automatically generates additional actions, such as payments and transfers of ownership without the middleman, Barcus says.

“Since smart contracts are code-based, it is far easier to change the rules by deploying a new, mutually agreed version,” says Barcus. “This approach not only reduces contract complexity and costs, it also provides critical flexibility to help support emerging new business models that aim to take rapid advantage of new market opportunities.”

Collaboration is key

One common thread in any digital supply chain initiative is the need to collaborate with supply chain partners—whether it’s blockchain or any other technology used to track products. When Dana McBrien worked as the associate chief adviser at Honda of America Manufacturing Inc. in Marysville, Ohio, he discovered that several other OEMs had embarked on a collaborative initiative to track returnable containers using RFID tags.

McBrien, now the guiding architect for the initiative at Surgere Inc., realized that if multiple OEMs worked together to develop a single standard solution, they could reduce complexity throughout the supply chain. Honda was trying to gain better visibility into the location of its packaging, McBrien says.

“In my 30-plus years at Honda, I saw the impact of initiatives by companies, and when different companies fire off the same initiative in different ways, that tends to make the suppliers’ jobs much more complex,” he says.

Surgere is providing the technology for the initiative, called AutoSphere. Members, which also include Toyota, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, Nissan and General Motors, are tagging returnable containers with RFID as the common technology to collect tracking information. The group has already notified more than 600 tier-one suppliers about expected deployment schedules, according to Surgere. When fully deployed, the group expects to reduce downtime and costs associated with lost or misplaced packaging, McBrien says.

Similar levels of collaboration will be needed to make widespread adoption of blockchain a reality, say industry experts. “For you to leverage blockchain, almost all the parties in your supply chain have to be on that platform,” says Zia Yusuf, partner and managing director and the global leader of Boston Consulting Group’s Internet of Things business. “If you’re a big company, you can encourage your supply chain to do that. But if you’re smaller company, that may be a challenge.”

Rio says as blockchain becomes more common, many supply chain partners may realize they don’t have much of a choice on whether to participate in the network. He likens it to the early days of email when some companies were still using fax, mail and phone calls as their primary means of communication. “If everyone converted to email and for some reason you didn’t, I don’t think it would be too long before people stopped communicating with you,” Rio says. “Once it gets to a critical mass, people who are not participating will be at a significant disadvantage.”

Three tips for getting started:

Embarking on a digital supply chain program may seem daunting given the scope of existing initiatives. Industry experts offer some insight on the next steps manufacturers should consider to make the autonomous supply chain a reality.

1. Demonstrate value. Onboarding suppliers may be easier if manufacturers can show shared benefits. Suppliers that joined Alpha Acid Brewing Co.’s blockchain network can raise their brand profile by participating in the program, says owner Kyle Bozicevic. “They know they produce a quality product, so they like the idea of receiving validation through our blockchain application,” he says. “It’s also an insurance policy for them. I can’t point the finger at their ingredients if I mess up a batch because the blockchain application proves the ingredients passed quality control on their end before coming to Alpha Acid.”

2. Start small. Have a well-defined scope that focuses on solving a particular business problem before launching an initiative, says John Barcus, vice president of manufacturing for Oracle Corp. “Don’t embark on a complete business transformation without first proving the value and understanding the costs,” he says. “In the early stages manufacturers should limit the number of trading partners.”

3. Choose partners carefully. The benefits of blockchain will only be achieved if it can process large volumes of data, Barcus says. “Ensure you are comfortable that your technology and partners can scale and deliver on enterprise-grade requirements to enable you to move seamlessly from a pilot to a production deployment.”